November 1-2nd | All Saints Day–All Souls Day

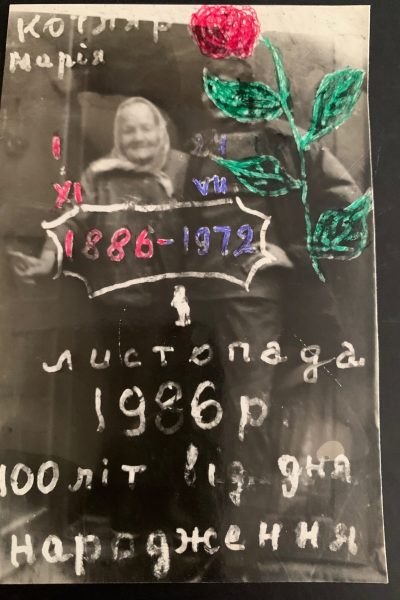

Maria Szajniak Kotlar was born on November 1, 1886.

Photo/text design by Pavlo Kotlar celebrating the 100th year of her birthday.

Maria Szajniak Kotlar

1.XI.1886 – 24.VII.1972

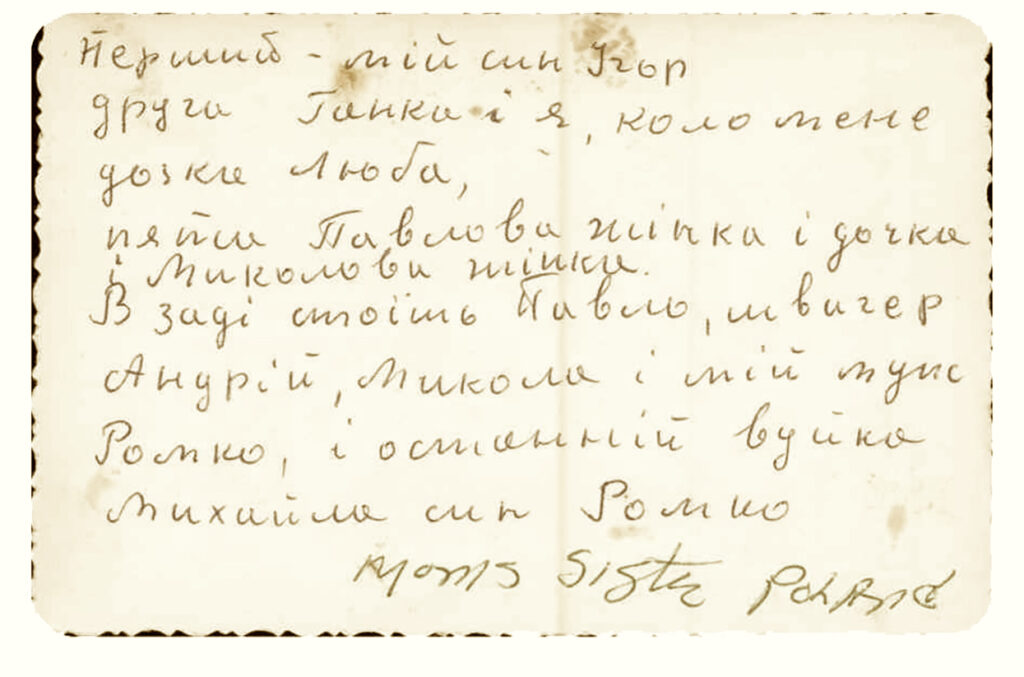

Above: Teta Maria’s handwriting. Translation: First row: my son, Ihor; Second is Hanka and me (Marika); next to me is my daughter, Luba; Next is Pavlo’s wife (Stefa) and daughter (Luba), and Mykola’s wife. Back row: standing: Pavlo, (brother-in-law) Andriy, Mykola, and my husband, Romko. Lastly, Uncle Mychajlo’s son, Romko.

Death, the Soul, and the Afterlife

In November, All Saints Day (November 1) and the next, All Souls Day (November 2), were significant holy days honoring the dead. In Ukrainian culture, death is viewed as a natural and integral part of human life. Ukrainians did not fear death and kept close relations with their dead, whom they saw as ancestors.

Folk beliefs about death, the soul, the afterlife, and various spirits date from the late 19th century, with the dead communicating with the living and vice versa through prescribed rituals. How people react to death, especially unanticipated death, reveals much about how they view life.

According to traditional Ukrainian folk beliefs, life did not end at death but continued, with death being another form of existence. Death was often perceived as a long sleep; “The person has fallen into an eternal sleep” meant a person had died. Folk understanding of a soul and its destiny was expressed.

Ukrainian culture surrounded human death with a complex of beliefs and omens. People imagined death to be an anthropomorphic being sending special warnings foretelling upcoming death, both one’s own and someone else’s. For many, death was a comforting, long-awaited event since they expected to reunite with deceased relatives immediately after death. Therefore, knowing the right time was important. Upon someone’s “good” death, the deceased’s family would call relatives and neighbors to help, and those requests were never refused.

Death was associated with dolia or a person’s destiny. The world of the dead mirrors this world in the Ukrainian folk imagination. It was perceived as a physical reality, with exchanges and transitions between it and the world of the living. Death was thought to manifest through birds– usually black or nocturnal- with unpleasant calls. People would pay special attention to warning signs, such as specific dreams that were believed to predict death, a knock on the window at night, or ravens, crows, owls, and magpies that circled above the house.

Memorials mark all locations where a person died unexpectedly. Countless beliefs, omens, legends, and tales characterized by magico-religious syncretism, magical prescriptions, and taboos surrounded the funeral ritual. A human soul after death was believed to be more magically powerful than a living person could ever be. It can overcome time and space restrictions, move about, do things beyond human capabilities, and acquire different appearances.

Church officials commemorated a deceased person on the third day after death, ninth and fortieth days. The next major commemoration came one year after death. The Sunday after Easter, also known as St. Thomas’ Sunday, проводи (hence the etymology – проводжати (to see somebody off), was the biggest memorial event, but only for those who had died a good death.

Source: The Structure and Function of Funeral Rituals and Customs in Ukraine

Natalia Havryl’iuk, Institute of Ethnomusicology, Folklore and Ethnography of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences