Village of Dudynce

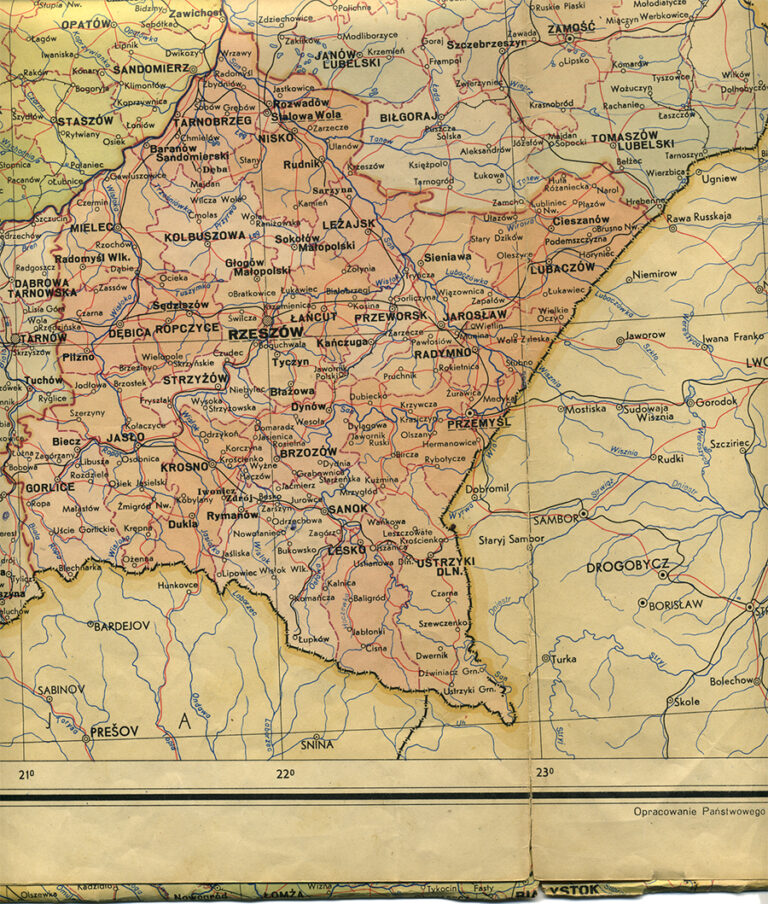

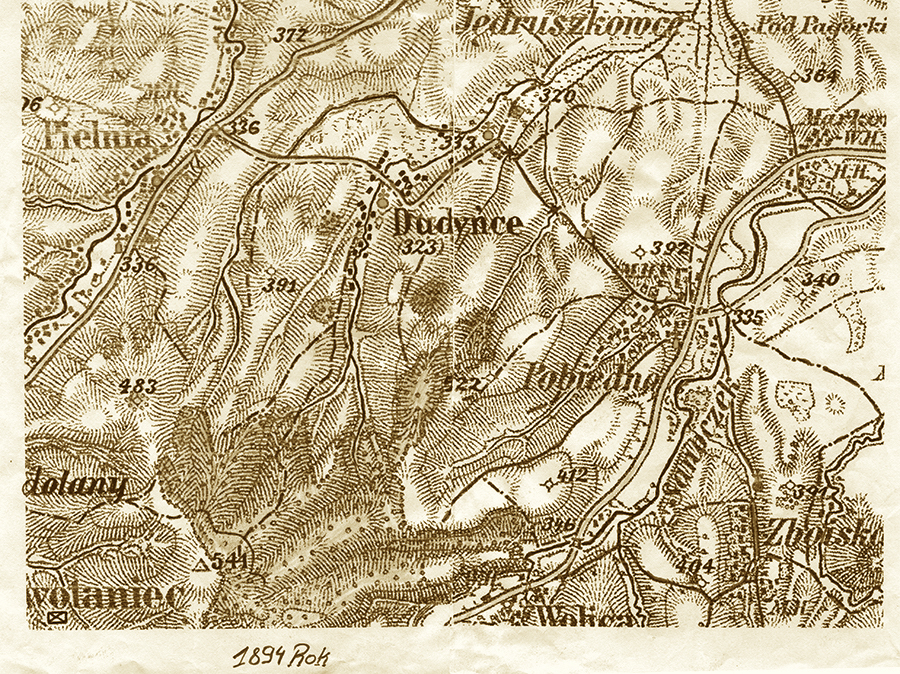

From 966 to 1018, Dudyńce was part of the Ruthenian Voivodeship (a province in Poland). According to some historians, Dudyńce was founded by Prince Władysław Opolczyk in 1372-1772. In some histories, Dudynce was considered Ruthenian, and was part of the Austrian-Hungarian empire from 1772-1918, and then part of Poland from 1918-1939. Dudynce was larger than a hamlet (a small settlement) but smaller than a town, situated in the Sanok District, ten miles from the city of Sanok, along the Sian (San) River. It’s a village in East Małopolska in the Beskid Mountains in Bukowsko, Dudyńce [duˈdɨɲt͡sɛ] in Ukrainian: Дудинці, Dudyntsi, Dwdinicze (1372-1378), Dudenycze (1436), de Dudenyecz (1448), Dudence (1678), a rural commune or parish.

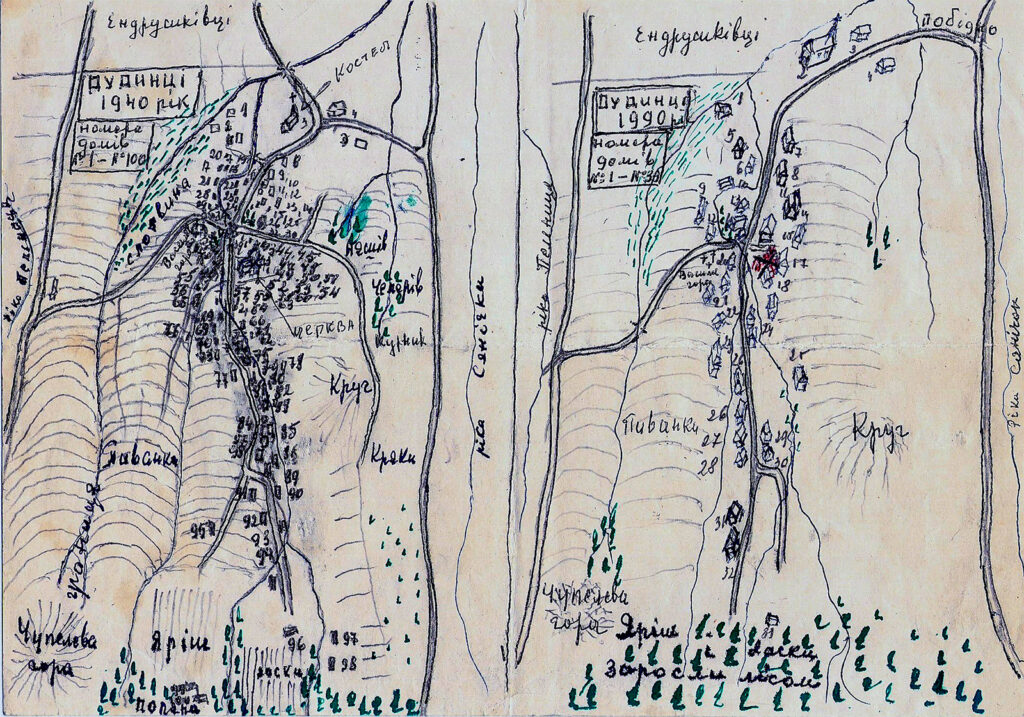

The village was ethnically mixed. There were Ukrainians, Poles, Wallachians (Romanians), Hungarians, Rusyns, and Jews. They had a Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in the village center and a Polish Roman Catholic, a Kostel, at the northernmost point. A community group looked after the village’s needs, and there was a reading room where news of the world was read aloud, and discussions were inclusive to all. Seasons were celebrated, holidays and Holy Days, and the weddings lasted three days. What’s it like to remember who your neighbors were? Where did they live? What happened to them in the aftermath of a historic 20th-century division– the Curzon Line– set arbitrarily but effectively and literally split the inhabitants into a divisive way of life during the Interwar Period (1930s). From the wanton destruction of attempted colonization by the German occupation during the Second World War to the forced deportation (Akcia Wisla) by the Polish Communists in 1947, ethnic Ukrainians were uprooted from their ancestral homeland and forced to move either to the Soviet-repressed Ukrainian SSR or to distant areas of Poland.

Pavlo Ivanovich Kotlar

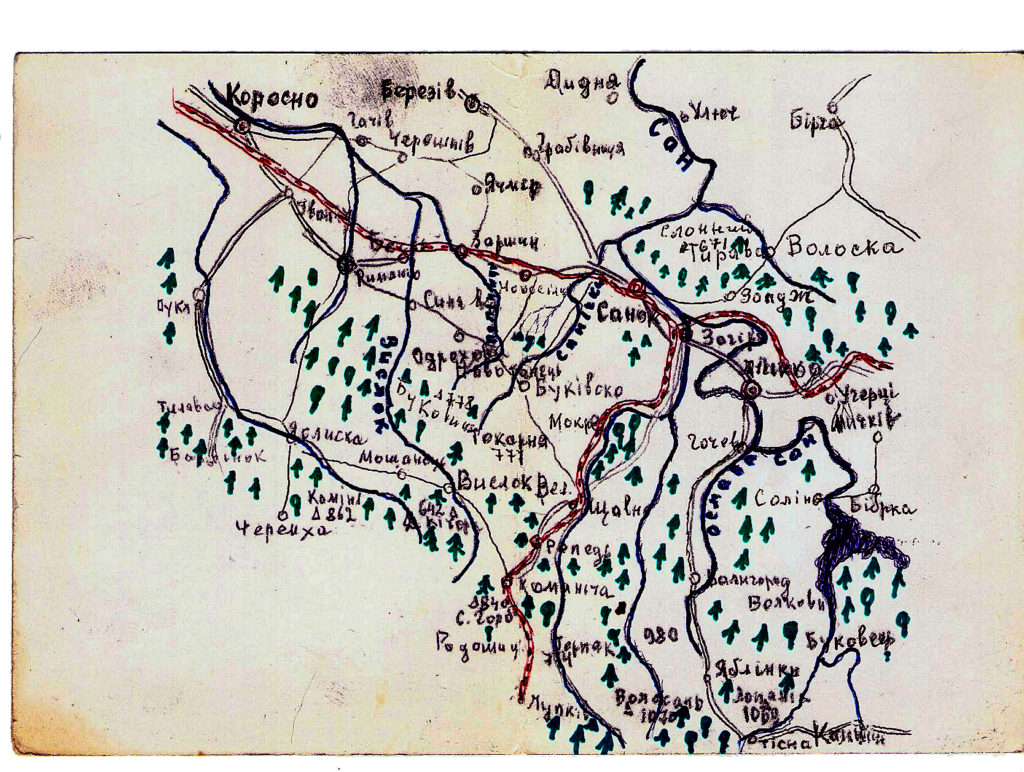

Pavlo, the fifth child and fourth son, was born to Iwan (Ivan/Jan) Kotlar and Maria Szajniak Kotlar in 1919 in Dudynce. He was a teacher in the village with a particular affinity for algebra and a penchant for drawing out maps of Dudynce and the surrounding area. In 1946-47, during the deportation of villagers in Lemvschyna, Pavlo stayed longer in Dudyce than allowed to help his traumatized neighbor. Little did he know that this act of kindness would lead to his arrest, trial for espionage, and a harsh sentence of twenty-five years in a Siberian labor camp. His arrest left a void in the family, with his absence was keenly felt by all.

He poured his heart into his letters, painstakingly drew maps from his memory, and listed names, describing daily life and family events and his deep longing for his beloved ancestral home. His letters are a rich tapestry of historical imagery, poignant quotations from Goethe, and a love for mathematics, as shown in written equations. He noted what had become of Dudynce’s inhabitants, providing a detailed account of the sociological upheaval of those who once lived there, i.e., one-quarter (25 families) were left in 1947—only two Ukrainian families.

Upon his return from exile, he lived with his wife, Stefania, and daughter, Luba, in Lviv, Ukraine, until his death on October 13, 2008.

Hand-drawn maps of the village shows its position and the vicinity (above) and the layout with the number of houses in 1940s (left) and the number remaining by 1990 (right).

1940s Map of Sanok District